"It is far better to be a resident on the brink of Hell than spend a lifetime in a relentless pursuit of a mythical heaven."

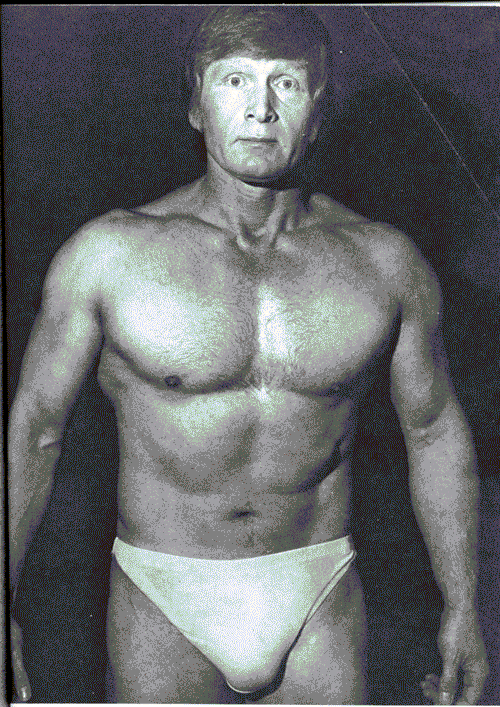

Okay, let’s have a show of hands here. How many of you have heard of Cliff Twemlow, whose quote that is above? Hmmm. Some have, most haven’t. Pretty much what I would have expected, really. How about if I told you he was a musician, a bodybuilder, a nightclub bouncer, a novelist, a screenwriter, and an actor? That ring any bells? No? None?

Okay, let’s have a show of hands here. How many of you have heard of Cliff Twemlow, whose quote that is above? Hmmm. Some have, most haven’t. Pretty much what I would have expected, really. How about if I told you he was a musician, a bodybuilder, a nightclub bouncer, a novelist, a screenwriter, and an actor? That ring any bells? No? None?

Well then, you’re just the kind of person who is going to need to see the

excellent new documentary Mancunian Man: The Legendary Life Of Cliff Twemlow by cult genre filmmaker Jake West

(Razor Blade Smile, Evil Aliens, Video Nasties: Moral Panic, Censorship, &

Videotape). The film premiered to a rapturous reception last August at London’s

FrightFest, gaining excited kudos and slowly and surely spreading the

reputation of the now-deceased renaissance man who is its bemused subject.

I’ve personally known of Cliff Twemlow since the late 80s, when I first saw G.B.H., (Grievous

Bodily Harm) the hardman Northern English bouncer film that cemented his brief,

quick-sputtering comet-blaze rep as a man and a strange force of nature to be

reckoned with. I was also aware that he had made a load of other films, often

unreleased, but this superb documentary really put together a load of jigsaw

puzzle pieces for me about the man’s somewhat…unique oeuvre and life in general. Here was a man who started off

in humble, impoverished circumstances, born in working class Manchester (hence

the film’s title, taken from the G.B.H. theme song), and who ended up living an

unprecedented life that was deranged and inspirational in equal measures.

When he wasn’t making music for telly programmes and getting sued by Cubby

Broccoli for ripping off a James Bond theme, he was lifting weights, writing

and starring in films, writing horror novels or memoirs…and on and on. But

first and foremost he was a filmmaker, proudly flying the flag for Manchester

and the north of England, at a time when everybody told him nobody outside of

London cared about the north of England culturally. It’s still relatively the

same to this day, but this obsessive, driven, never-stopping, energetic

middle-aged trailblazer helped bring a bit of flash and glamour and sizzle to

the north for a change.

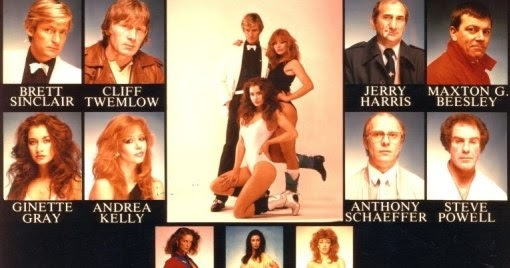

In the meantime his productions involved the likes of Charles Grant, Oliver

Tobias, Fiona Fullerton, and Joan Collins, using everything from purloined Bond

film cars to a giant killer pike and face-eating aliens to cause fun movie

chaos. Twemlow certainly wasn’t out to be a po-faced kitchen sink drama

merchant.

If this heretofore-buried slice of retro English cultural treasure sounds like

your thing, or even if you just like hearing about unique characters, you have to see Mancunian Man. By times

hilarious, totally mental, fascinating, poignant, deeply sad,

and inspiring, it will raise emotions in you that you never even knew you had

towards a long-dead, larger than life English cinematic hustler-cum-bodybuilder.

Mancunian Man is, quite simply, one of the best cinema documentaries I have seen

in years. I found it totally entertaining from start to finish, and sometimes

scarcely believable in how bizarrely surreal it got in places. I would urge any

lovers of genre cinema, oddball eccentric one-off characters, and filmmakers

who often managed to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory, to definitely give

this fine film a look. You won’t regret it.

Anyway, with that said, Who Rattled Your Cage interviewed Jake West about his crazy new genre doc baby. Take it away, Jake...

Anyway, with that said, Who Rattled Your Cage interviewed Jake West about his crazy new genre doc baby. Take it away, Jake...

Graham: You know what? You have done

Cliff proud. Your documentary is superb, man, I thoroughly enjoyed every minute

of it.

West: Oh thank you so much, that’s

lovely to hear. I mean, we’ve had an amazing response since the Frightfest

premiere, and everyone’s really loving it. As a filmmaker that’s always a

dream, that it connects with the audience. And Cliff’s story, I think because

he’s such an interesting person, and he’s one of those, you know, great British

one-off true originals, so it’s really fascinating to learn about somebody

really like him, and a part of British film history that a lot of people really

knew nothing about. So it was fascinating, kind of digging into his story.

Graham: How did you first become

aware of Cliff’s work, and what was it that appealed to you about it?

West: Well, I really first became aware of Cliff's work when...I dunno if you know the Video Nasties documentaries that I did, for the Video Nasties sets we did for Nucleus (Films). When we were doing the second one, Cliff's film G.B.H. was a Section Three Video Nasty-

Graham: Yep.

West: - So we did a whole piece

about G.B.H. at the time. To do that piece we interviewed CP Lee, and he’s the

guy in the documentary who wrote the book The Lost World of Cliff Twemlow with

Andy Willis. And when we spoke to CP, we were obviously covering G.B.H. But I

had no idea Cliff had done all these other movies and all these other things, a

lot of which had never been seen. So CP was banging the drum and going “Oh

yeah,” cos he absolutely loved Cliff.

He was like the first person in the UK who really wanted to revive interest in

Cliff. And obviously subsequent to that, CP Lee has died himself a few years

ago, he’s no longer with us, a bit like Cliff he never got to see how this has

snowballed. There’s bits of that original interview that we did for the Video

Nasties set in the documentary plus we also found some other archive footage

which another documentarian had done with him, a guy called Stephen Crompton

had filmed an interview with him as well.

He was originally trying to put together a documentary about Cliff, but like a

lot of things in Cliff’s life (chuckles) that never happened. We were fortunate

enough to get a hold of some of his CP Lee footage, so we used some of that in

there as well. So yeah, it was really through CP Lee and the Video Nasties that

I became aware of Cliff and G.B.H. And then I was aware that he had done all of

these other films, but it wasn’t something you could easily get a hold of and

see, because a lot of them were unfinished. I knew a few people who had seen

like G.B.H. 2.

There were copies of some of them floating around, but they were hard to find.

And it was only three years ago when David Gregory at Severin Films got in

touch with me, they’re putting together a set of a lot of Cliff’s stuff and

they wanted me to do a documentary about it. That hasn’t been announced yet,

but that will soon be announced, what exactly they’re gonna release, because

they’ve been securing rights and all the rest of it for a bunch of Cliff

movies, so it’s gonna be like one of those Severin Special Editions (chuckles

gleefully).

Graham: Do you want me to leave that out just now, then?

West: No, you can say that

that’s what’s happening, but we can’t announce exactly the whole package. We

will be able to at some point, but they need to get all of their ducks in a

row. But that’s coming down the pipe, so you can mention it. You can say it’s

yet to be revealed, but it’s gonna be pretty special, I can tell you. (Chuckles)

(Mancunian Man will receive a digital release from Severin Films in June 2024 - Graham)

Graham: I actually contacted Steve

Powell back in 2004-

West: -You wrote that interview

with him, didn’t you, the one where they’re in Africa?

Graham: Yeah.

West: It’s a nice interview, I

really enjoyed reading that, which I did during the research period on this.

http://www.jeet-kune-do.info/steve-powell/african-skies

http://www.jeet-kune-do.info/steve-powell/african-skies

Graham: I was going to say to you, he actually sent me all of those tapes

on VHS nearly twenty years ago. Since then I moved to America, I got rid of a

lot of stuff. But he sent G.B.H. 2, Firestar, all these movies at his own

expense, such a kind gentleman. He even sent me his copy of Tuxedo Warrior to

read. Really kind, good gentleman.

West: (Grinning eagerly, but

instantly in inquisitive documentarian mode) Do you still have those tapes?

Graham: No, erm…I was actually thinking about this when I was watching the

documentary, because I’m thinking, I gave all my VHS to my cousin Michael

Allan, I’m going to have to ask him if he still has them, he might or might

not.

West: I’ll tell you what, if you

could look into it, because we’re still trying to find a version of G.B.H.

2…there’s two edits of it, two cuts. There’s the Lethal Impact with all the

flashbacks in it, but then there was an original edit of G.B.H. 2 which doesn’t

have the flashbacks in it, which is a shorter and a different edit. We’re still

trying to find a good copy of that. We’ve only got a really bad copy of that

edit, so if your cousin’s got G.B.H. 2, could he have a look to see whether

it’s the Lethal Impact cut, or the original one?

Graham: I’ll ask him. Though as I said, it’s 2005…

West: I know it’s a long shot,

but we’re still really…

Graham: Long shots sometimes come up trumps in the strangest ways.

West: (Grinning widely) Yes, exactly. So since you’ve mentioned that, I

just thought I’d chase that up. I’m always fishing, cos we’re still trying to

find that specific edit, you see. (Laughs)

Graham: I understand, trust me, I understand the elusive Grail quest for

some obsessive talisman in your work. (in the end the print turned out to be

the same bad quality as the one the filmmakers already had, but it was a nice

dream while it lasted – Graham)

West: Yeah, I think in a way his

is the whole thing about, ummm…in the modern world. It’s obviously been a lot

easier to get a hold of pretty much anything you want on the internet now. But

with Cliff, there still is an element of Grail questing to finding decent

versions of his films. So perhaps he’s one of the few filmmakers where you

still have to work quite hard to find a decent copy of his work. (Laughs)

You might be able to find stuff online, but it’s pretty shoddy, a lot of it, so

we really are doing our best. Because one of the main challenges with Cliff’s

stuff, a lot of it was shot on video and the masters were poor to start off

with, so it’s not like you’ve got 35mm film that you can scan, you’ve got video

copies of things that aren’t great quality. So we’re doing our absolute best to

really restore, and get the finest quality we can for, you know, the Severin

release. Same with the documentary, actually, we had access to some amazing

footage, and Marc Morris has been working on that, my partner in Nucleus Films.

Graham: I loved the animations in the film, they were really, really good.

West: Well, that’s the wonderful

Ashley Thorpe, the director of Borley Rectory. Ashley is an amazing animator,

and he’s a good friend. And when it came to “we really need to bring these

things to life, to have these animated sequences,” when I asked Ashley

(grinning widely), every time he was doing an animation I just couldn’t wait

for him to send me the next one. (Excitedly, grinning widely) It was like

having a preview of a special little kind of movie about Cliff. So yeah,

beautiful work from him, there.

Graham: I really like your enthusiasm, by the way, obviously for the

material. What was it about the movies that appealed to you, or what was the

whole…

West: As, I say, learning about

Cliff, I guess, because I’m a filmmaker and I’ve come up through making low

budget films myself. Like my early movie Razor Blade Smile was shot on 16mm,

with a crew of six people for twenty grand. So any filmmaker will understand

the beats of Cliff’s difficulties, in terms of him being a filmmaker.

Especially when he was working at a time in the 80s when it was very hard to

make a film. And the fact that he decided to do it on video technology as a

sort of a work-around for him to get his films feature-length and do stuff.

Obviously there was a diminishment in quality. But it still wasn’t easy for to

get things shot and edited at that time, because the equipment was so different

and clunky and analogue. So I think I have a genuine appreciation of somebody

who kind of fought the odds. I mean, he wasn’t trained as a filmmaker, I mean I

went to film school and I’ve been making films as a teenager. Cliff was a

(laughing) bouncer, you know, a doorman and a bodybuilder.

So the fact that he got enthusiastic about filmmaking when his Tuxedo Warrior

got made, based on his book, (laughing, making ‘inverted commas’ sign with

fingers) very loosely, he then had all of that enthusiasm. And

I think that the thing about Cliff, the more you find out about him, you can’t

help but admire his sort of tenacious, dogged enthusiasm despite it all going

wrong a lot of the time. And I think that’s the thing, filmmaking is a tricky

business, y’know, so you kind of like him a lot more cos he (grinning widely)

kept on going. I think he’s inspiring, even though he wasn’t a massive success,

I still think his story is very actually very inspiring.

Graham: He reminds me of Rudy Ray Moore, that whole thing.

West: Yes.

Graham: I mean, you’ve done a really comprehensive job, you’ve got photos

of Cliff as a child, you’ve got all the information about his dancer mother and

his seaman father, you’ve painted a really comprehensive portrait…

West: Well like I say, this has

taken us three years, and we did a huge amount of research. We tried to get in

touch with everybody. Pretty much all the people in there, you could say “Well,

why didn’t you interview Joan Collins?” Well, we offered, we spoke to her

agent, and once again she wanted twenty grand (laughs) or something. We just

couldn’t afford to do that. Similar thing with Fiona Fullerton, she just didn’t

want to talk about it so she just said no.

We basically tried to get every single person attached to that stuff. So, you

know, it wasn’t through want of trying, believe me. I wanted it to be as

well-rounded and as comprehensive as possible, I certainly didn’t want the

documentary to be saying “Cliff is great,” it was looking at him and his flaws

and how he did things wrong, and that’s what makes the thing interesting to me.

I don’t like the kind of corporatised puff pieces where it’s just people saying

“Oh, it was so wonderful doing it.” You can see that clearly everybody had a

great time doing these films, but often the results were far from successful.

Graham: Well that’s the thing. When you watch the documentary you get that

Cliff is very driven, you know. But he’s also kind of self-destructive in a

way, because he just keeps jumping from project to project to project. And he

doesn’t really give himself the time to get the thing finished, and get more

money coming in. Why do you think that was? Why do you think he just kept going

and going and going? Do you have any thoughts on that?

West: My thinking is that Cliff

didn’t like the business side of it, and he wasn’t very good at that side of

things. I think he loved to be kept busy, I think he liked doing stuff. And I

think he had the vanity to be ‘the star,’ and he wanted to be in the films. I

think he enjoyed galvanising people, I think he enjoyed having a company of

people around him, and hence that’s why all his friends continued to work with

him over the years. I think he really enjoyed being almost the head of the

family, do you know what I mean? But I think from that perspective he really

just enjoyed doing things. I think he just enjoyed the rush of the filmmaking,

but then the reality of the post-production, and trying to get distribution,

stuff like that, I don’t think that he really seemed to want to give that the

right amount of time.

And it’s a shame, obviously, because if he had had a couple more successes then

it would it would actually have made his production side easier. But that’s the

impression I get from doing the documentary, that he was in love with the

process off, the actual making of the films. But then beyond shooting, I think

he lost interest a bit and just wanted to do the next thing. That’s the

impression I get from it. It’s almost like a guy on a sugar rush, maybe because

he was a bodybuilder (mimics lifting weights) he was all about the result of

doing the thing. But then he just wanted to get back down the gym.

Graham: Yeah. That’s an interesting analogy. I mean, obviously if he’s in

post-production he’d be sitting in some editing room with whoever, but he’s not

going to be able to show off his muscles in front of the camera, so why bother?

West: From talking to people,

the impression I got that in terms of the post, Cliff wasn’t that interested in

sitting in on the edit, he would maybe stick his head in and have a look at

what they would be doing, whereas they would just be working all night. So he

needed people to facilitate that side of it. But a criticism of his scripts is

that he didn’t spend enough time writing them, enough time focussing the

stories, and in the same way he didn’t spend enough time in post-production

actually crafting the work.

He was a lot more about the rush of the making, so I think he enjoyed the

performing side a lot more than he did the technical side of things. As a

filmmaker he should have, you know, looked at what his weaknesses were and

tried to improve on those things. So you could argue maybe he wasn’t

self-reflective enough in terms of his own career, about where he was trying to

go. But it’s also possible because he was doing this stuff in Manchester, and

there wasn’t a lot of people interested in anything coming from the north of

England, certainly at that time. One of the reasons his stuff didn’t really

catch fire is that he was from Manchester, and the Mancunian accent didn’t

travel that well beyond, kind of, you know, (laughs) kind of Salford.

Graham It occurred to me, just thinking there, that I wondered if it might

have been to do with his age. You know, he’s getting older and just wanting to

make stuff.

West: He was obviously very

concerned about his age, hence him hilariously saying he was older so that

people would say he was younger. But perhaps he needed to have started a bit

earlier, perhaps he started a bit late. He must have been in his, I dunno, he

was probably in his forties when he started.

Graham: I think he was forty-five when he made G.B.H.

West: He seemed really conscious

about that as well. So, you know, if he had started in his twenties perhaps it

might have been a very different story, I don’t know. This is one of those

things about Cliff, he never quite had all of the ingredients, but what he did

have (laughing) he made the best of. But he mentions his age in most of the

films. I think that was something he was definitely conscious of, you’re right, you

know. In Eye Of Satan, “How old are you,” he’s asked, “Old enough to smoke,” he

says.

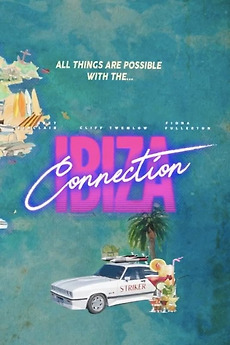

He does make reference to his age a lot in the films. Similar in The Ibiza

Connection when he’s going out with the younger girl, he talks about the

autumn-slash-spring relationship that they’re in, and she’ll move away from

that. I think there is this continuous reflection, I think that probably

something that he was bothered about. And certainly, towards the end of his

life, when he was obsessively training and entering these competitions, and he

started to fail and got into steroids, unfortunately I think that side of his

personality – his concern about his age and his looks – is the thing that

really did undo him in the end, sadly.

Graham: In the film you talk about a north-south divide. You’ve got

Manchester, then you’ve got north England, then you’ve got London. But he did

do a lot to put Manchester on the map, you know. You talk about every gangster

film that comes since has had G.B.H.’s DNA in it.

West: Oh no, absolutely. Cliff’s

aim was to make Manchester the Hollywood of the north, that was his stated aim.

You’ve got to admire him for that. One thing about Cliff, he was incredibly

loyal – he was loyal to the people he worked with, and he was also loyal to the

place where he was from. And he was very proud to be a Mancunian, hence the

film being called Mancunian Man.

We wanted to celebrate this idea, that somebody in Manchester in the 1980s, a

time when the north of England wasn’t being taken seriously as a creative place

– you had the birth of Granada TV and he was part of that. So I feel that one

of the things he actually did succeed in was maybe changing some of those

attitudes in Manchester. And he was certainly one of the few filmmakers in England

actually making movies at that point, and creating this mini film industry in

Manchester. So that was something where I think he was successful, and ahead of

the curve, definitely.

Graham: I agree entirely with that assessment. Have you spoken with, or

have you heard of filmmakers who have either directly or indirectly cited him

as an influence? I mean, he must have influenced you in some way, you know?

West: Once again, by the time I

got to hearing about him I’d already made Razor Blade Smile, Evil Aliens and

Doghouse. So he wasn’t an influence to me directly, but indirectly I found his

story inspiring. I think there may be some filmmakers in the north of England

that were more influenced by him, because CP Lee used to do these Twemfests

back in the day, you know, back in the 90s. He would show these films to films

students because he was a university lecturer, and he had Cliff on his syllabus of

teaching. There was a group of film students in Manchester who did learn about

Cliff, so he may have influenced some of those people directly. And I think

that would be interesting.

But now that Cliff’s name is gonna be spreading a bit wider, perhaps we’ll

begin to hear more about people who he has actually influenced in a real way.

To me, I find Cliff an inspiration cos of the way he approached stuff. That I

really liked, and found him a larger than life and fascinating character. I

think in filmmaking, to succeed, you have to be a little bit larger than life

anyway, and you need to have some force of personality to actually get through

the fucking door, certainly back in

the day.

Nowadays it’s a lot easier due to digital technology, and the fact I could go

make a movie on my phone (waves phone in front of webcam) now, and I could edit

it on my laptop. The point is that it’s so much easier now to make a film,

whereas back in those days it was really difficult. Cliff identified the things

that he was good – i.e. fighting, the physical side. He was smart enough to

know that him and his friends weren’t great actors, so he played around with

action films and horror films. But he wanted to make stuff which was commercial

and unpretentious, and I think that says a lot about Cliff as well.

The mainstream British industry at that time were not really interested in people

who wanted to make commercial or unpretentious work. If Cliff had been making

films about poverty in the north, he probably would have been taken seriously

by the BFI types.

Graham: The usual po-faced, miserabilist shite.

West: Exactly. And Cliff certainly

didn’t represent that. And that’s something I really like about him, the fact

that he ripped off James Bond films, y’know, really crap, bizarre, fun horror

films. Ibiza Connection is like a meta comedy when you look at it, it’s a film

about a film being made. That was a bit ahead of its time, there wasn’t

anything else like that that I’ve seen that was made at that time.

Graham: The film previous to that had a lot of problems, and he might have been inspired to write this behind-the-scenes thing...

West: Absolutely. Cliff definitely drew on things he knew, and the fact that Eve Island was such a disaster, and the next film being a film about an action film that goes wrong, surely Eve Island was the inspiration for Ibiza Connection, definitely.

Graham: Yeah. To assimilate something

that just happened to you, and to put it out is kind of post-modern in a way.

That’s sharp thinking, that’s very…

West: The thing about Cliff (twirls

finger round head to show cerebral gears turning) is that he was always looking

for an angle on stuff, you know, like G.B.H. 2 with the paedophile ring, which

is a very dark subject. That was an idea he had had for the film, oh god,

what’s it, uh…

Graham: Blind Side of God.

West: Blind Side of God. So that

idea was something that he’d worked on five or six years earlier, and

eventually that became G.B.H. 2. But he was looking at something that was very

provocative in the media at that time and obviously it’s very dark. And you can

say, okay, he’s using it in an exploitative way, and he was, but he was still

trying to pin something on something that would get a reaction from people.

He was a thinker, Cliff, on that front, definitely, looking for trends, maybe

sometimes setting them, like in the way he produced his films. So you could say

he was interesting for a lot of different reasons, especially given his

background, being a working class guy who had no sort of direct access into

this world. (Laughs)

Graham: Even when he was writing…I

mean, he wrote Tuxedo Warrior, he wrote The Pike, he wrote The Beast of Kane,

I’ve actually got a copy of Tuxedo Warrior myself…

West: Tuxedo Warrior is a great

read, in a way, it’s really interesting. It’s very funny as well, you can

really get Cliff’s sense of humour. I had to shorten this film, because the

original edit was a lot longer, I had to get things in, it was about four

hours, the original cut. There’s loads of stuff that was in there that I had to

take out. Like The Beast of Kane, for example, at one point that had been

optioned by Hammer, but it never went ahead. It’s one of those things that…if

it had gone ahead, and that happened, then that could have changed Cliff’s

trajectory once again. So there’s all sorts of things in Cliff’s like that almost worked out but…didn’t quite. (Laughs)

Graham: Well he was obviously

following, as you point out, the 70s horror paperback trend, the Shaun Hutson

and the James Herbert kind of thing, “I’ll just sit down and I’ll write one of

these sort of things.” I mean, you’ve got to admire the balls on the man for

just doing it.

West: He never seemed to be fazed by

the idea of doing something, whether it’s writing a book, whether it’s the

bodybuilding, whether it’s making a film, whether it’s writing music. Once

again, he wrote over two thousand pieces of music, but he wasn’t a musician. (Laughing) He used his

“dum-de-dah” technique (Twemlow used to hum and mutter tunes to himself – Graham)

and got other people to record them. Even that was strange. And that was the

thing about Cliff – even though he was limited, he still found a way to do things. And I think, once again,

that’s to be applauded, because he did so much.

Graham: I agree a hundred percent

with you. I’ve been a Cliff fan for probably…in the late 80s my friend Scanny

and I used to trade on the underground horror circuit, y’know…

West: (Laughing and nodding in

recognition) Oh yeah, back in those days…

Graham: “Send us a copy of

Re-Animator with bits cut out of it, and inserts in black and white”. (Jake

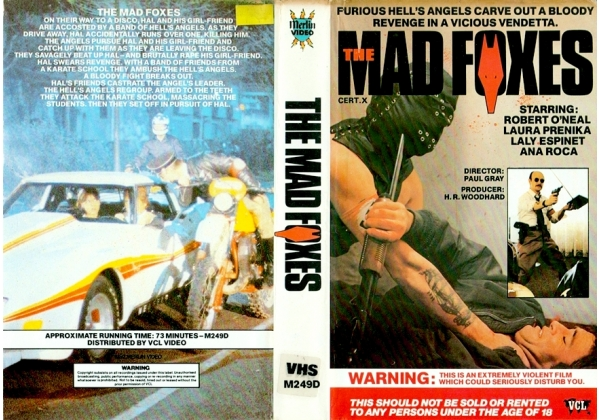

laughs in recognition) I’m more of a kind of trash fan, I liked Mad Foxes and

Suffer Little Children…

West: Yeah yeah. That’s another

shot-on-video one, isn’t it, Suffer Little Children?

Graham: Terrible film. Terrible film.

West: (Laughing) Yeah.

Graham: But it was Scanny that gave me G.B.H., "It's not my kind of thing," he was more into Dario Argento and Lucio Fulci. I just watched G.B.H. and it I just instantly took it to heart. There's a guy who's a friend of my younger brother's from school, Ross Graham, I kind of look on him as a younger brother. He moved down to Brighton, and when he came back up to visit me in Falkirk we'd just sit and watch G.B.H. together. It's a tremendous film, it really is.

Graham: But it was Scanny that gave me G.B.H., "It's not my kind of thing," he was more into Dario Argento and Lucio Fulci. I just watched G.B.H. and it I just instantly took it to heart. There's a guy who's a friend of my younger brother's from school, Ross Graham, I kind of look on him as a younger brother. He moved down to Brighton, and when he came back up to visit me in Falkirk we'd just sit and watch G.B.H. together. It's a tremendous film, it really is.

West: (Grinning widely) It’s incredibly entertaining, isn’t it. I mean that’s

the thing, it has got a sense of fun about it, and a warmth. Also, its

genuinely of that period. You know, when people are trying to recreate the 80s

and that, it never feels quite right. But that was something really from

Manchester in the 80s. It’s a window into the past as well, but with humour and

those kind of characters. So definitely, (chuckles) it’s a wonderful film.

Graham: Well, I think that covers it, Jake, thank you for your time.

West: Feel free to email me if you want me to expand on anything

Graham: Thanks very much.

THE END

Mancunian Man: The Legendary Life Of Cliff Twemlow will receive a digital release from Severin Films in June 2024. Before that, you can see the film in a cinema:

26th April 2024 - Prince Charles Cinema, London + Q&A with Jake West

https://princecharlescinema.com/PrinceCharlesCinema.dll/WhatsOn?f=30647938

4th May 2024 - Glasgow Film Theatre, Glasgow + Q&A with Jake West

https://www.glasgowfilm.org/movie/mancunian-man-the-legendary-life-of-cliff-twemlow-qa

Bonus random obscure Cliff clip:

And finally, one of the best clips on Youtube:

RIP CLIFF TWEMLOW: 14/10/1937 - 5/5/1993

"Nobody dies forever" - The Mancunian.

"Nobody dies forever" - The Mancunian.

Comments

Post a Comment