(Photo: JG Thirlwell)

In

1980, in the still-smouldering post-punk ruins of London, a strange,

many-headed sonic hydra was immaculately conceived. This miracle pregnancy

would bear deranged audio fruit in 1981, with the release of the first 7”

release from a multi-moniker noise myth that would eventually come to be known

as simply Foetus. The father of the ectopic uterine disaster is Australian

James George Thirlwell, one of the world’s top avant-garde composers.

A crosseyed

drooling, hyena-laughing beast of blackly comedic revelation and dysfunction,

Foetus would continue grow and churn out singles and albums under a motley

clutch of slippery monikers over the coming 43 years, eagerly assaulting unwary

and confused listeners with a bombastic, shrill frenzied assault of every musical

style known to man. And that’s before even mentioning the ever-evolving

Thirlwell’s endless sonic mutations in other elite art projects and

installations: Manorexia, Steroid Maximus, Volvox Turbo, Xordox, Baby Zizanie,

Wiseblood, and on and on.

What

ties all these styles together is the unique disparate quality of the music,

from noise rock to classical to swing to experimental, mixed in with the

artist’s peerless poetic lyrical flights of violent fantasy, sexual frenzy,

anger, depression, rage, hubris, hatred, self-loathing, slaughterhouse laughter,

narroweyed political observation, madness, and tragedies and triumphs of the

will.

Wordplay

and stream of consciousness and quips and puns and pop cultural references and

highbrow literary nods and lowbrow splatter movie grue and true crime and

childhood chants and frightening noir prose poetry all coagulate over forty-odd

years to provide a perfectly-deformed inkspiller Rorschach of the

sleight-of-hand writer and poet grinning darkly behind their abortive creation.

One minute we have a sly bastardisation of a line by Bob Dylan, Shakespeare, or

the Beastie Boys, the next it’s an Evil Dead dialogue insert mixed with a

nursery rhyme assault, topped off with a stark murder ballad throat-slice power

couplet.

It’s a

magpie-ear bitches brew of lyrics that read like nobody else’s output, to my

eye and mind at least. Whilst I have seen Thirlwell (who is by now known

interchangeably as Foetus) discuss his musical methodology many times, I have

never seen him discuss his lyrical work, which is something this interview

attempts to remedy a bit. After all, in 2025, the final Foetus album, Halt,

will be born and die, eternally accessible vibrant stillbirth tracks smeared in

the musical monster’s messy wake. This will bring a by-then 44 years of utterly

unique words and tunes to terminal term, though no doubt Thirlwell will

continue abnormal service as unusual for other projects.

So I figured now was as good a time as any to snap on surgical gloves and gown and perform a gutty sloppy Caesarean section on the proud parthenogenesis-fuelled father, starting toothily severing the umbilical c(h)ord, grinding through the chewy blood-pumping gristle, asking Thirlwell about his writing style in Foetus and in other projects. What rough sonic and lyrical beast, its long-gestated hour come round at last, slouches towards New York still to be born? I guess we’ll find out soon enough…

Graham: What was the first thing you can remember writing,

and reading, and what was your youthful taste in books?

Thirlwell: Oh, you mean back in my childhood?

Graham: Yes.

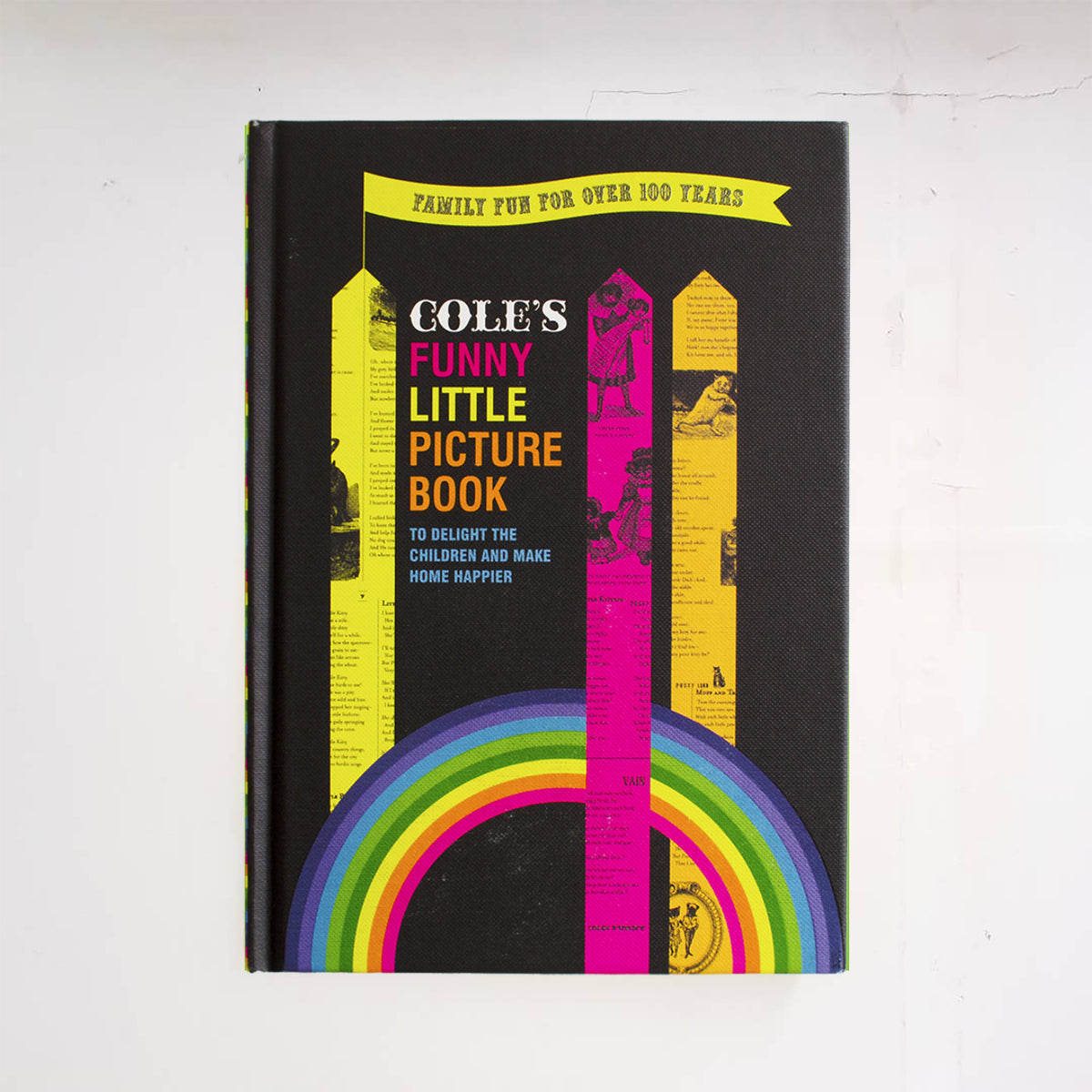

Thirlwell: Oh, um…the first stuff was obviously kids’

books, I remember reading Doctor Seuss. And also, my aunt was a speech teacher,

and she had a lot of books. I remember, like, there was a lot of Victorian type

of kids’ books, things like Peter Rabbit and earlier than that. Those type of

books. And then there’s a lot of weird arcane Australian kids’ books with

strange, unsettling illustrations like Snugglepot and Cuddlepie, The Bunyip and Cole’s Funny

Picture Book.

I was an avid reader through my childhood and I’m still a

pretty avid reader. When I was in school I studied English literature, and so I

got through a lot of things voraciously. Through my teen years I was reading

stuff like, say, Kurt Vonnegut. And then I discovered existentialism and I was

reading Albert Camus and Simone de Beauvoir. I would go on binges of things

like that. And I read a lot of the classics as part of my school, like Chaucer

and Shakespeare, Emily Bronte and Charles Dickens. But then a lot of the pop

stuff from the era I was growing up in, like Norman Mailer, things like Fear Of Flying, Catch 22 and Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s

Complaint.

There was sort of a broad swathe of stuff. I would think “What

are the classics I should have read?” So I was reading that sort of stuff when

I was fifteen and sixteen, you know. I felt like I was filling in a lot of my

education with that. And now I go back and think that I’ve read a lot of things

that are considered classics, but then I see holes…like I’ve never read Crime and Punishment, I’ve never read Ulysses. Later on I went through a binge

of reading true crime, then I went through a binge of reading noir, Jim

Thompson and stuff like that. Everything by Hubert Selby, Harry Crews, Charles

Bukowski. I keep filling in more holes in my reading. This year I read two

Patricia Highsmith books back-to-back. I still read a lot.

Graham: I mean, that comes through. I was actually going

to ask you…you know, in some of the songs you’ve got the kind of hard-boiled

defective detective thing, the vocab (Jim nods), “the woim toins,” “fiddling

while Rome boins.”

Thirlwell: Yeah.

Graham: Is that from your kind of Jim Thompson detective

phase?

Thirlwell: Well, those actual lines came before my Jim

Thompson obsession, and that noir obsession. It was a noir thing, but it’s not

what I was reading at the time. That came a bit later. I like a lot of the

terminology, it’s just so engaging and hilarious a lot of the time, those sort

of turns of phrase. And also, of a totally different time.

Graham: Yeah.

Thirlwell: I just read this book by James Cain, I can’t

remember which one it was, it was one of his famous ones. But it’s written in

the thirties, and some of the language in that, and the depictions of the

relationships you just would not get

away with now. It’s really extraordinary, you know.

Graham: Is that maybe The

Postman Always Rings Twice?

Thirlwell: That’s exactly what it was, yeah.

Graham: I jokingly mentioned the Rimbaud joke from Lust For Death on your Facebook page-

Thirwell: -Oh yeah.

Graham: -And you indignantly said that you knew how to

pronounce Rimbaud, because you did five years of French.

Thirlwell: Yes.

Graham: I was actually joking, because I knew you would

know how to pronounce ‘Rimbaud’. (In the great song, Thirlwell rhymes the

French poet's name with ‘limbo’ – Graham).

Thirlwell: Yeah, that’s kind of a ridiculous rhyme, you

know.

Graham: Well it’s about Iggy Pop, and he’s quite a bookish

character when he’s not being completely mad.

Thirlwell: He’s very intelligent.

Graham: Oh yeah, you can tell 100%, he’s a character. Now,

there’s two songs that I noticed you sing in a foreign language – this is jumping all over the map

with my questions – one is Mon Agonie

Douce – not sure of the pronunciation. (Thirlwell nods) And the other is La Rua…

Thirlwell: La Rua

Madureira, but I didn’t write that one.

Graham: No. (as I discovered in researching the interview,

Nino Ferrer wrote the song – Graham)

Thirlwell: I wrote the music for Mon Agonie Douce and just felt that should be sung in French. And

so I wrote the words with my limited French, and then I had a French-born

person I know look at it and just adjust my grammar and things like that. And

I’m writing another French song now for an as-yet-untitled album I’m doing in

collaboration with (American composer) Simon Hanes. They are songs for the

female voice. Just because it really feels like it should be in French. But I

might sort of co-write that, because it’s going to be really complicated to

nuance of what I want to say in that. I went on a deep dive about Serge

Gainsbourg, because I love his work. I started reading a French Gainsbourg

biography in the original language and then I gave up, thinking this is going

to take me a year to read. I also wrote a song in Spanish. I don’t speak

Spanish at all, but I had a Spanish translator translate it for me.

Graham: You do have a facility with language. I mean, was

that song, Mon Agonie Douce (I

pronounce it ‘douche’ and laugh at myself – Jim nods – Graham) “My agonised

douche!” You said you wanted to write it in French. It seems like a heartbreak

song, right, the guy’s angry about having his heart broken.

Thirlwell: Yep.

Graham: Love and romance

are not the usual Foetus subjects to sing about, except in more negative ways

about interpersonal relationship troubles. Would you say you’re shy in singing

about these things?

Thirlwell. I’m not really shy

about writing about those things but I’m more interested in other subjects. The

world already has a lot of songs about love.

Graham: Now, I want to tie this into something. Lydia

Lunch said of you that you’re reserved, sensitive and introspective, right?

Thirlwell. (Noncommittally) Hmmm.

Graham: Now I can believe that one hundred percent. But

lyrically, your main themes, I would say, of your work, are alienation, extreme

mental and emotional torment…

Thirlwell: (Nodding) Mmm.

Graham: …religion…

Thirlwell: (Nodding) Mmm.

Graham: …and there’s a kind of fairground approach to

sexuality, a kind of Grand Guignol, cartoonish use of sex…

Thirlwell: (Nodding) Mmm.

Graham: Now, with Mon

Agonie…and I’m not going to say the last word again, cos I’m not going to

embarrass myself…is that an image that you’ve constructed for yourself

aesthetically, from words, like a broad sweeping image, that you don’t like

going against?

Thirlwell: Oh no, that’s not true at all. I do think that

those things that you mentioned, that’s true, especially of my early work. I

think something like Mon Agonie Douce,

I chose to sing to in French because I felt more comfortable saying what I was

saying in that song in French than I was saying it in English. It is pretty

confessional, and it’s not the sort of song that I normally write in terms of

the lyrical content. But I think that if you really wanted to put a broader

kind of global conception around what I’ve done, I would say that a lot of my

work is about politics.

And in the earlier work it’s more about personal

politics, like the politics of relating in society and so on. And the later

work is more about party politics. It’s more about universal themes and what’s

happening in the world in the last thirty years. What’s ironic is that some of

the songs that I wrote for the last Foetus album, which was Hide in 2010, the content of those songs

are just impressions, they’re still applicable today. But we’re in a different

political climate, we’re on different administrations, we’re in different wars,

but it’s the same thing.

I think it’s important to sometimes de-specify what

I’m talking about a little bit so the song doesn’t become dated. There’s a song

I’m writing at the moment for the new Foetus album, which is a little bit more

time-specific, y’know, about what’s going on now, and will probably date

itself. But normally I want to keep it a bit more universal. And I don’t deny,

especially off my early work, there’s a certain amount of…shock value in some of the songs.

There’s confrontational elements and transgressive elements. Because I was

coming out of the punk revolution, if you want, and through Dadaism and

surrealism, and using this art form as a form of confrontation. ln addition I

was taking a contrary viewpoint, where I would embody a character in a song,

and what that character was espousing was actually the opposite of what I

thought.

Graham: (Nodding) Aye, so you were being your own worst

enemy then.

Thirlwell: I was being the Devil’s Advocate, yeah.

Graham: I haven’t heard all of your early work, but I was

looking at some of the lyrics again today, like Mother, I Killed The Cat (the B-side of the 1982 Phillip and his

Foetus Vibrations 7” – Graham), you know, bleak but hilariously funny.

Thirlwell: Yes, the title came from a film.

Graham: Some of the things you’re saying are tallying up

with certain things I was going to ask anyway. Are you able to follow me okay

when I’m speaking, I’m trying to enunciate each verb and vowel for the

accent-uneducated ear.

Thirlwell: My mother’s Scottish…

Graham: (Chuckling ruefully) Aye, that’s true, we’ve

talked aboot that. Right. You went to London in 1978, right?

Thirlwell: Yeah.

Graham: And you first recorded Foetus in 1981, it was O.K. Freeze Mother-

Thirlwell: -Well I recorded it in 1980, actually, it came

out in ’81.

Graham: Right. What I was going to ask is this. You’re

clearly a very literate, poetic person, you have an admiration for the written

word-

Thirlwell: Mmm.

Graham: -that’s very obvious. There’s every kind of

literary and poetic technique known to man in your early work, and right

through. You’ve got stream of consciousness, you’re playing with words, kind of

Joycean. But it’s interesting that you mentioned Doctor Seuss, because I can

see Doctor Seuss in those early lyrics as well, you know, (Thirlwell sits with

hand on chin, pondering, or maybe just being polite - Graham), that word-bounce

and flow, but which is also quite Joycean.

Thirlwell: (Long pause) Hmm…

Graham: (Laughing) Lyrics that you haven’t thought about

for thirty years..

Thirlwell: (Nodding indulgently) Ummm…yeah. I mean, I

can’t see the through line to Doctor Seuss, apart from the fact that he makes

things rhyme. I wouldn’t say that he was one of my muses.

Graham: No, but talking about rhyming…complex rhymes,

surrealist, absurdist, the way that he does that sort of thing…don’t worry, you

don’t have to admit to a sort of (laughing) Doctor Seuss fetish.

Thirlwell: There’s a lot of pop culture in that early

stuff, too.

Graham: Yes, there is.

Thirlwell: And it’s unbridled, you know, it’s real stream

of consciousness, those cultural references. But I’m interested in form, and

internal rhymes, and also the times when you don’t rhyme. You know, cadence is

very important in carrying a song, the vowels that you choose are important in

carrying a song, too. So those are all things that have to be considered,

although on the early stuff, probably the first ten years, I never really sang

the song before I got into the studio and put on the headphones and did the

vocal. I wrote the lyrics in advance but had never put it to the track. Now I

really try things out, and I have a lot of different ways of approaching

lyrics.

Graham: So what would these

new different ways be, any examples?

Thirlwell: I know many people

do this already, but I've started putting down vocals with a hand held mic, and

sometimes starting with pure phonetics just for rhythm and melody. I fill in

the words later.

Graham: Now, I keep going back to this, but…in 1980, you

say you recorded the first Foetus single, and it was released in 1981. So you

had a couple of years there, 78-80, where you were…what, just starting to learn

how to record, or write lyrics?

Thirlwell: Yeah, well…78 to 80, when I arrived in London I

was just finding my feet, I would go out to see a lot of music, I originally bought

a bass guitar and a synthesiser and I was making music in my room, and

eventually got together with pragVEC, which turned into Spec Records. We did an

album, and making that album was kind of what made me realise I didn’t wanna

work in a democratic way, I wanted to work in a way where my ideas succeeded or

failed on their own merits, so that I didn’t have to accommodate other peoples’

ideas. Also in that period I started working with Steve Stapleton from Nurse

With Wound, and that was very pivotal for me. So there was plenty happening in

those eighteen months before the first Foetus record emerged.

Graham: Were you writing lyrics for songs, though, before

the Foetus material?

Thirlwell: Yeah, well, I’d written a couple of stupid

songs earlier on. No, I wouldn’t say I had a body of lyrics, I was kind of

writing them for the projects, y’know. I always had notebooks with ideas in

them. I don’t remember that the books had writing in them, I think they

probably had a lot of drawings in them.

Graham: What was the

writing in the insert for Nail, that

you said you wrote in Helsinki jail? Was that just a way to expand on what the

songs were about lyrically?

Thirlwell: Yes, it was to

contextualize the through lines of the songs. The connective tissue was oppression.

Graham: You see, that’s what strikes me when I go back…and

I did go through every lyric of yours that I could find, there are very, very

few holes in the thing, which is good, but…it did strike me that right from the

start your lyrics are fully formed. That it’s not just some dilettante thing,

where you’re obviously feeling your way over years to be able to produce some

sort of usable lyric. It wasn’t like you were learning to write in front of

everybody, you are very clearly a poetic and literate person, your love of

words comes through.

Thirlwell: I was definitely learning in front of

everybody, and I think if I was to go back and evaluate…well, I am gonna do a

book of annotated lyrics-

Graham: Aw, brilliant, brilliant!

Thirlwell: -and I think some of the things I would go back

and find a bit cringey, but a lot of the stuff isn’t cringey as well.

Graham: No, it absolutely is not!

Thirlwell: Yeah.

Graham: There’s amazing stuff there! I mean, you’ve

got…sometimes it’s just like stream of consciousness, but you’ll randomly throw

in a bit of Shakespeare. Or free association, too, you’ve got “oil flow,

Orwell, or well.”

(Follow this link to the second part of the interview: https://whorattledyourcage.blogspot.com/2024/10/bringing-foetus-to-halt-part-2.html)

Good interview. I remember you from the old SWMB.

ReplyDeleteHuh, funny. I remember you too, Mike. Hope you are well.

Delete