Graham: Then you’ll talk about a random bit of British

politics, albeit there is not very much British politics in your lyrics for

five years in the country. But it’s all part of a one, it’s still very

literate. The words are very sharp, it’s not like you don’t know how to write.

You clearly know how to write. You ever want to be a writer, an author, do you

have any old novels that you’ve stuck away in a trunk somewhere, from high

school years?

Thirlwell: I’m going to be writing a memoir, I’ve started

laying the foundation for that. And I don’t want to use a ghost writer, I’d

like to do it myself. I’ve been reading a lot of musicians’ memoirs just to see

what’s out there, how people are doing it. And so that’s been another journey

I’ve been on for the last couple of years, researching all of that. But no, not

really, I don’t think I have a novel in me. I’m not really that interested in

doing that, you know. There are stories that come out from my music, but

they’re not really as fully formed as a novel would be. I know people who are

novelists and I don’t wanna (shaking head) go down that path, it’s pretty hard.

I mean, as you know.

Graham: Yeah. You’re like a shark moving through chummed

sonic waters, right.

Thirlwell: Mmm.

Graham: If you’re a novelist you’ve got to sit down for

six months or a year…I won’t even tell you how long it took me to write my

fucking book (Soundproof in Satellite

Town – Graham), to get rid of it. But it doesn’t strike me that you’d be

comfortable in that kind of environment, where you’ve sitting writing and

rewriting something, because you’re so constantly on the go.

Thirlwell: I did spend years at a time on very ambitious

projects, but I found as part of my work practice that I really value nibbling

at things. As long as I’ve started doing something, I can do a little bit of it

here and there and let it build up. Otherwise…I wouldn’t wanna say “Okay, I’m

gonna spend the next six months writing a book.” Because I can’t just do one

thing, I can work on the book for an hour, then I can work on a piece of music,

or work on three different projects. I have to work on many different things at

once, and one thing informs the other.

Graham: That very much comes through in your approach to

putting out multiple records every year, y’know, and collaborating with people,

you’re very restless in that respect. It does strike me that if you’re going to

put an hour or two a day into a novel…it depends how long it’s going to be, and

what the subject matter is...you know, the lyrics that you’re doing are almost

like cutups (the random writing style invented by William S Burroughs and Brion

Gysin, by way of Tristan Tzara – Graham), you’re all over the place. It’s

fascinating. I mean, I’ll buy your bloody annotated lyrics book, because really

it’s fucking…amazing lyrics. You

told me in an email years back that you stopped kind of writing in that wordflow-bounce

way because everybody started writing that way, do you remember that?

Thirlwell: No, what was that there?

Graham: Nah, you just said to me, you thought that people

were starting to write a lot more like you were writing, so you stopped writing

like that. Like, even in…I can’t remember…I’ve got the song title someplace,

I’ll put it in the story… but your delivery almost sounds like proto rap. Were

you aware of what was going on in New York at the time, and listening to that

sort of stuff?

Thirlwell. Oh yeah, I was very much so, yeah. On the first

Foetus album, Deaf, there’s a song

called Today I Started Slogging Again-

Graham: That’s it! Yes.

Thirlwell: -which is about the Marquis de Sade. It says

(recites rap style) “I am the M.A.R.Q.U.I.S. D.E. S.A.D.E.” (Laughs) Yeah, I

was very into hip hop when it started. I was working at a record store, and

there was a certain point in time when you could actually own every hip hop

record that had ever been made. This was in the late 70s or something, because

there weren’t that many of them. It was really exciting, and when that record Grand Master Flash On The Wheels Of Steel

came out and it was just all turntablism...that blew my mind, that someone was

doing that with turntables. But yeah, I thought that that was exciting, the

early hip hop stuff. It had certain conventions that they don’t do now. I liked

hip hop right up until the 90s. Right now I think, since the 2000s, I find

mainstream hip hop to be a bit reactionary, a bit samey and can’t handle the

sing-songy autotuned hooks. But I think that there are interesting things

happening on the fringes of hip hop. But. You know, all pop music is pretty

much hip hop now, or hip hop in form.

Graham: Aye, it’s very boring, but when I was listening to

(Today I Started Slogging Again) it

was very obvious, I thought “Ah, I recognise that style of flow and delivery.”

Thirlwell: Yep.

Graham: But you always knew you were heading to New York

anyway. You’ve got New York Or Bust,

where you’re extolling the virtues of someplace that you know you’re going to

somehow.

Thirlwell: No, New

York Or Bust was actually facetious, and it became prophetic.

Graham: Well, exactly.

Thirlwell: I was happy to be in London when I wrote it. I

didn’t know I was staying in New York until I got here, and then I fell in love

with the place and just didn’t want to leave.

Graham: Well, I suppose I’m imposing a retrospective

interpretation, because I know about the last forty years of your life and

where you ended up. So it’s just funny to look at that lyric and see…where

obviously you are taking the piss a bit, “where David Byrne buys his shoes,” all

that kind of stuff. But there’s still this kind of…intrigue

there about the city, you know?

Thirlwell: Yep.

Graham: I have two intertwining questions here: who are

any of your favourite lyricists, and what makes a good lyric to you?

Thirlwell: (Puts hand to chin, pondering) Favourite

lyricists? (long pause) Hmmm. Jeez, that’s a hard one.

Graham: (Grinning) Good!

Thirlwell: Favourite

lyricists. (Still pondering with hand on chin, looks down at floor)

That’s interesting, you know, because (chuckles in bemusement) it makes me

think that I may not know other people’s lyrics that much. My girlfriend has

Apple Music, where they have a feature where you can turn on the lyrics and

they scroll, you know. I put on this Queens of the Stone Age album. I really

like them, and I was watching, reading the lyrics as they were scrolling. And I

realised I had no idea what

the hell he was talking about, I had no idea what those lyrics were or what he

was singing until I saw them there. I

don’t particularly know what he’s singing at all. Probably generally I would

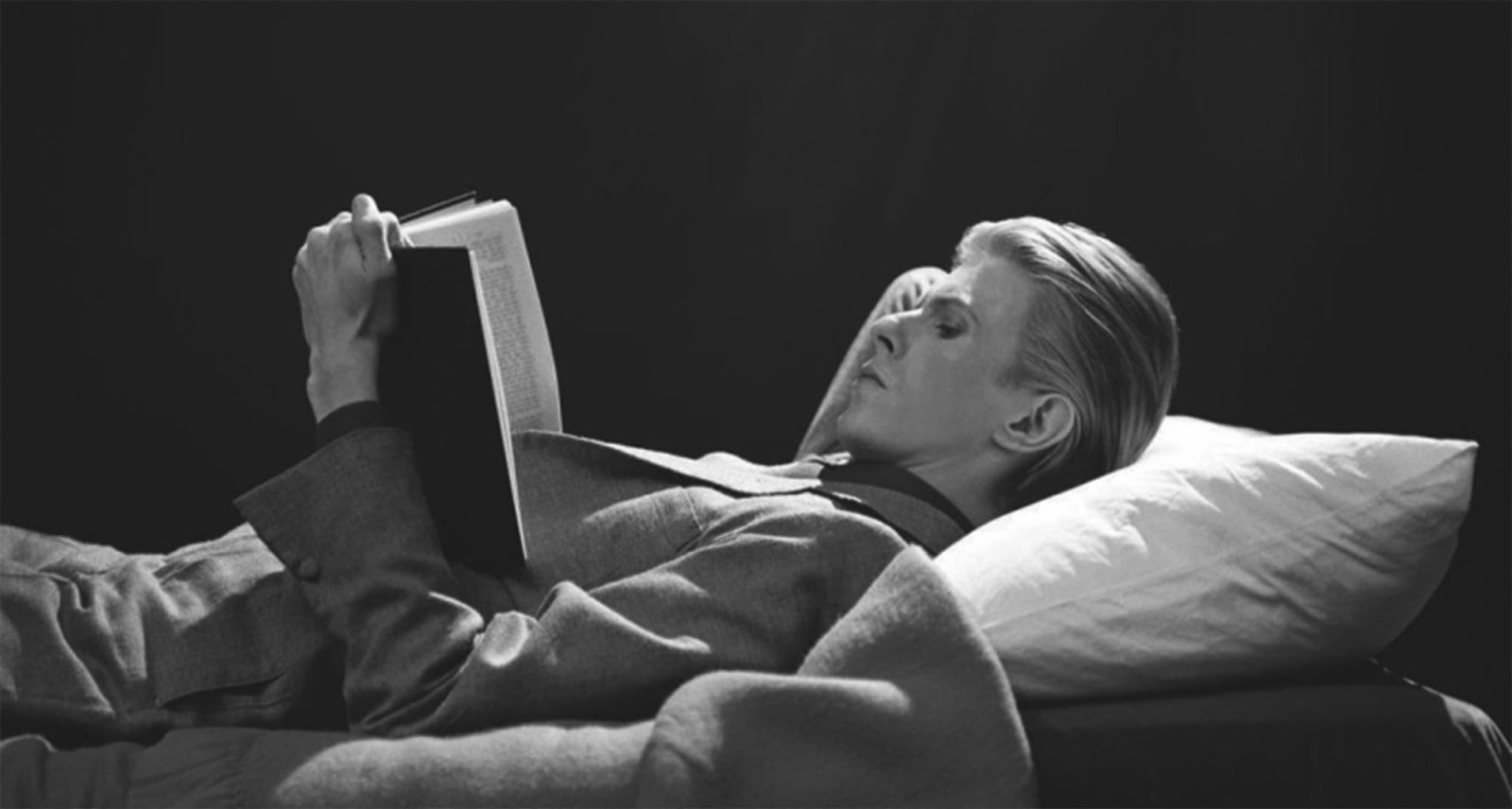

have to say that the person who’s written the lyrics that’ve had the most

impact on me has been David Bowie.

Graham: Oh, okay, right.

Thirlwell: Probably because of the time that I discovered

his work, and the amount that infiltrated me, infiltrated my DNA. I think I was

much more conscious of lyrics at that point in my life, between the ages of ten

and…twenty, maybe, or something. And those words have gotten into my DNA, and I

still think he wrote great words because he wasn’t there to draw in something

abstract because it sounded good. That’s not something that I do too often. But

the things that he threw in really painted a picture. So probably David Bowie

has had the most impact on me lyrically.

Graham: Your answer to that question was quite interesting

because you had to think about it. I’m the complete opposite, I’m a total

wordslut. I can tell if I’m gonna like a band if I like their words. I’m the

kind of person who will sit on Genius and pathetically correct lyrics if I know

they’re wrong, because they’ll stick in my craw. But I find that interesting

because you are sui generis, if that’s the pronunciation, your lyrics…

Thirlwell: A lot of the music I listened to was

instrumental as well.

Graham: Well I was going to say…obviously you’ve got that

orchestral theatrical musical streak…what about musicals? Any musicals that you

like the lyrics from?

Thirlwell: I’m not really into musicals. I know a little bit about them, but I’m more into them maybe a little ironically, I guess? I do like the musical forms, and I do think that there are some clever lyrics in those old musicals, but they don’t resonate with me. Recently I’ve been writing some songs that do reference musicals and that type of form, but with a totally different message. But I couldn’t hold up a musical and say “Yeah, I really like the words on this.”

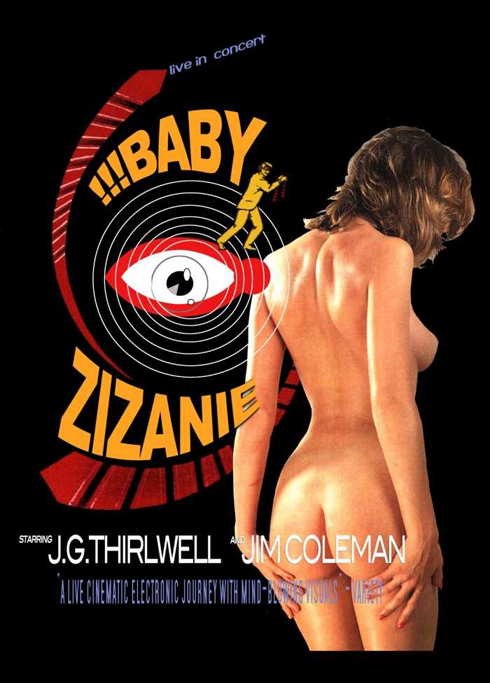

Graham: I noticed that when you started off Foetus…I mean, you’ve had different projects here and there, Wiseblood, Baby Zizanie, and a million other things, you were much more verbally based. Your use of words has really decreased over the decades.

Thirlwell: Yep.

Graham: Your work is pretty instrumental now. Is there a

reason for that?

Thirlwell: I think…yeah…there’s a couple of reasons for

that. When I started Steroid Maximus my music with Foetus was becoming

increasingly more instrumental. Like fifty percent of the album was

instrumental, and I decided to break it away and start an instrumental project.

And then fast forward to, say, 2001, I started Manorexia for a somewhat similar

reason. I wanted to get it out of my system, using a different idiom, using an

instrumental form that was maybe more spacious. That carried on its own path,

and that sort of took me into the classical world a bit, the commissions

(Thirlwell has done various commissioned musical projects round the world –

Graham) and things like that. (Pauses. My image has frozen on the Skype screen

he is looking at) You’re frozen, can you still hear me?

Graham: I can still hear you, yeah. Doesn’t matter, as

long as I can hear you.

Thirlwell: Yeah. But also, around 2001, 2002, was the last

time I toured with Foetus as a live band, a kind of rock band. And I had

already been feeling that Foetus as a live band was an inadequate vehicle for

my music, it didn’t allow me to put enough of the nuance into the music that

was in the recorded versions. And by the end of touring, around 2001, I said

“That’s over, I don’t want to do that anymore, because I think it dumbs down my

music, that’s not what I wanna do.” And around that same time I got

commissioned to create a large ensemble for recreating a Steroid Maximus album.

And that was where I felt “Okay now, I’m finally hearing my music in real life

like I want it to be.” And that was all instrumental. But around that time I

was also beginning to feel like…maybe singing songs is a bit stupid?

Graham: (Laughs)

Thirlwell: And I kind of do feel that a little bit, still.

I think there’s validity to it, there can be. I’ve been writing songs for other

people to sing, and in some ways I prefer that. You know, writing the music and

the lyrics, performing it, saying “Here, this is how it goes, let’s hear you

sing it.” Because I don’t want it to be in my voice, I want to write for

someone else’s voice. It’s taken me a while to get back to where I am writing

for my own voice. It was hard to think, what do I wanna say? Like right now I’m

working on this Foetus album , which I’m planning for it to be the final Foetus

album. And so I wanna close the arc, I wanna close the circle on what started

in 1981.

You know, when people get to the end of their lives and they say they

wanna put their affairs in order. I want to put Foetus’s affairs in order, I

wanna be the one to say “Yeah, this is how the story ends.” And so there will

have been ten studio albums which were all conceived as a stand-alone thing

unto itself. There’s also been remix albums and compilations and live albums

and satellite albums and so on, but this will be the tenth specific studio

album. And so I’m thinking about like, okay, how do I wanna end this story?

First of all, each time I do a Foetus album I wanna reinvent music and I don’t

want to repeat myself. There’s gonna be strands of a continuum because that’s

me. But I want to move the narrative forward, and also…what do I wanna say

lyrically? Because in some ways I do want to reference what I’ve done in the

past on this album. I wanna tie the whole thing up. And so what would be an

album to tie everything up – but in 2024, you know? And I think I’ve finally

gotten to it. I’ve finally got all the songs written. I started it about six years

ago and I’ll finish it this year. I’m really happy with where it’s gone

lyrically. I think it’s really an important chapter of my lyrics, and I’m

really proud of the way that they’re turning out.

As I said before, the

political thing is pretty strong in this. There’s one song that’s specifically

about the pandemic, from that time. The Foetus album that came out in 2005 was

called Love, and I chose that title because it was the most unexpected title

for a Foetus album you could imagine. But it was kind of about love, and it was

about what I was going through in my conflicts, and it was about internal

relationships and love as a struggle and wrestle with humanity. And I think

I’ve learned a lot more about that subject as I’ve gotten older. And then the

subsequent album I feel had a lot of dread in it.

And this album has even more

dread in it. The previous album had the dread that was the product of the

George W Bush era, and this one has the dread in it from the Donald Trump era.

The dread is similar, although this one is much more extreme. You saw that JG

Thirlwell + Ensemble show in London (I attended the show and met Thirlwell backstage on 12/8/2023 - Graham): that has given me a chance to revisit a

lot of lyrics from the arc of my career. One of the songs we perform is from

the next Foetus album. And then the earliest song that we perform is I’ll Meet You In Poland Baby, which I

wrote in 1983. So that’s more or less a forty-year arc of writing. When a lot of the volume and pummelling from

the live band from before is stripped away, the lyrics are more naked like

that, and it makes them feel much darker and more naked, you know?

Graham: The way you’ve been progressing lyrically has

become a more certain, specific thing. The vocabulary you’ve been using with

Manorexia, or other outfits of yours…you’ve got ‘dinoflagellate blooms’,

‘ataxia’, ‘mesopelagic’, ‘anabiosis’, ‘bruxism’, ‘hydrofrack’, ‘kinaesthesia’,

‘dystonia’, ‘omniverse’, ‘oscillospira’, ‘thalassophibia’. But they’re all

instrumental pieces.

Thirlwell: Yep.

Graham: Do you find that you just use those as a guide for

yourself, or for the reader – sorry, the listener, I apologise – and do you

ever just mischievously put on a random title on that you think has nothing to

do with the content of the song, the music?

Thirlwell: Oh yeah, all the time. I mean, because I always

have to have a working title for a song, I don’t want it to say Song Number 39 or something, I always

think of a title, and sometimes that title sticks, and stays there. For example

(not adam), which was on one of the

Foetus albums (Love – Graham), was

just a title for the music that I started. And the place where the title (not adam) came from was from the author

Adam Thirlwell.

Graham: (Laughs)

Thirlwell: You know who that is?

Graham: No, I just got where the (not adam) would come from, that’s all.

Thirlwell: Yeah yeah yeah. So, say you put ‘Thirlwell’

into a search engine, at that point Adam Thirlwell was coming up. And so I put

‘JG Thirlwell (not adam)’, that’s

what that references, it references Adam Thirlwell. I’ve read one of his books

to see what he’s all about. I dunno if we’re distantly related. Are you aware

of him?

Graham: (Chuckling) Nah, maybe his next book will be

called (not jg)!

(Follow this link to the third and final part of the interview: https://whorattledyourcage.blogspot.com/2024/10/bringing-foetus-to-halt-part-3.html)

Comments

Post a Comment