(This post contains explicit language, disturbing thoughts and lyrics and images, and references things like self-harm and suicide. Be warned.)

“Deliver me from this treachery

Deliver me from this agony

Stop trying to make a man of me

I ain't got the raw materials, see?”

- Scraping Foetus Off The

Wheel.

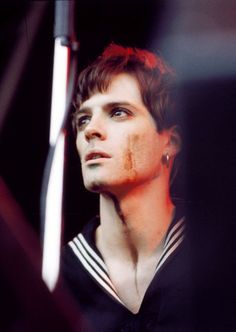

OK. Today, February 1st, 2025, is the 30th anniversary of

the disappearance/suicide of Richey Edwards, the lyricist, guerrilla-chic

peacock, and quiet-tuned guitarist for Welsh band Manic Street Preachers. On

this sad anniversary, I am going to do a dissection of Die In The Summertime, a

breathtakingly strange and disturbing and oddly beautiful song from their

classic album The Holy Bible.

I have been listening to this horrific brutalist work of transcendent sonic

genius since it came out in August 1994. It’s one of my three all-time

favourite albums. The other two are equally dark – Fresh Fruit For Rotting

Vegetables by Dead Kennedys, and Nail by Scraping Foetus Off The Wheel – but

they have many more moments of sanity-saving levity in their pockmarked

track(mark)s. You can make of my taste what you will, but neither of the latter

albums bears the same legendary weight and heft and pain-load of The Holy Bible;

practically no other album ever recorded does. Anybody who knows the history of

the work knows why, and it can be learned easily on the net. This is not a

beginner’s class. I am only going to do one song because, to me, it’s the best

(and eeriest and most tragic) tune on the album, on an album stuffed with

madness and mass murder and mutilation and mayhem. It's totally unique, and one of my all-time favourite songs. After this, I have nothing

further to say about this band or album. Thinking about it a lot is not good

for the head or heart.

You may ask why I am doing this. Well, I am asking myself the same thing, to a

degree. I am not entirely sure, and it’s not just because it’s an important

anniversary in the whole unholy Holy Bible saga. I know this is an album I have

turned to during bleak, inkjet-black periods of my own life, able to relate to

the bends-inducing depths of depression and intellectual screaming on it. For

me, listening to it is a genuine catharsis, down to the tag team horror-etching

lyrical duo of Richey Edwards and Nicky ‘Wire’ Jones. The music is top notch as

well, of course, and the album rocks like a grinning ear-pummelling bastard.

If a man tragically died in the making of this album, then at least something positive can come of it, and people can draw strength and purpose from it. Believe it or not, and I am not joking here, I genuinely find it uplifting to listen to and sing along to this album. The Holy Bible has held me in a brain-stuttering death-trance many a weird, obsessive time, I freely admit. It's just that feeling of liberation from fucking...everything normal and sane and right, ultimately. In my own extended family, and circle of friends, I, like many, have experienced incidences of self-mutilation and alcoholism and drug abuse and, yes, suicide. A relative of mine has disappeared and we unfortunately don’t know if he is dead to this day. That...wondering never goes away entirely. So there are a few things on the album I can relate to. And a helluva lot more I can’t relate to, thankfully. That’s more than enough motivation explanation to be getting on with.

NO ONE KNOWS THE HELL WHERE INNOCENCE DIES

"Genius is childhood recalled at will" - Arthur Rimbaud.

Here’s the (in)famous song itself:

The above paragraph, taken from a 1994 interview with Japanese music mag Music Life, is what Richey Edwards said Die In The Summertime is about.

Which is complete and utter nonsense, of course.

Another quote, this time, from the album’s tour programme:

‘Condition of old age – youth always remembered fondly. OAP wants to die with favourite memory month in mind. Adult memories tawdry, of little value.’

More nonsense, of course, mixed with some truth. I know I personally have many adult memories that are neither tawdry, nor of little value, and so do you. To suggest anything else is just melodramatic and petulant and teen-angsty.

But why is it nonsense? Well, for a start, the first quote mentions autumn and fallen leaves and snow. None of these are in the song. It’s summer, remember? In the second, it’s says that the OAP wants to die with their ‘favourite month in mind.’ The thing is, the whole song is completely contradictory, from pleasure to pain to confusion to dissociation to detached mockery, and none of it truly adds up to youth being ‘remembered fondly.’ We will explore this shortly. In the meantime…

“This lyric actually does scare me. I didn’t bother asking Richey what this was about, I was like, ‘If you know, I don’t want to know…’ I remember seeing the title and thinking, ‘It’s that tension in the words: ‘Die – in – the – summertime.’ Like, Tropic – of – Cancer. The tension of opposites, innocence versus the reality of the world”

– James Dean Bradfield.

So the band’s singer, who was normally extremely fastidious about knowing the ins and outs of a song so that he could write music for it, and sing on it properly, didn’t want to know what his friend and band member meant by the lyrics in the song. An attitude that seems oddly irresponsible, in some ways…but who can blame him? The song is incredibly grim, bizarre, frightening, cold, and viciously loathing, of self and of others. It’s also dark eerie superb fractured poetry.

Also:

“It was one of the first songs we wrote for the album, and I found it pretty disturbing when Richey first showed it to me. Now, of course, it’s even more so, and I think this and ‘4st 7lb’ are pretty obviously about Richey’s state of mind, which I didn’t quite realise at the time. Even if you’re quite close to someone, you always try to deny thoughts like that”

– Nicky Wire.

So we have two separate other members of the band recoiling from the song lyrically. Don’t worry, we will get to the words in a moment. Once again, who can blame them? These were young (early 20s, though Edwards was a year or so older than the other three) guys from a Welsh mining village that became post-industrial when they lived there, destroyed by the scum Thatcher and the Miner’s Strike. They were not born and bred and raised in an environment that found time for discussing mental and emotional problems, certainly nothing like today, where things have almost pendulum-swung to the opposite extreme.

This random violence deeply ingrained itself in the band, imbuing their records and actions with a deep need to antagonise and alienate. But deep-dish discussions about self-mutilation and mental illness and anorexia and alcoholism? Not really on the daily menu. Which was ironic, given that they grew up alternative-culturally on “slut heroes” offering “a fear of the future,” every romanticised-self-destructive musical or literary nutcase (Hendrix, Pop, Morrison, Curtis, Bukowski, Moon, Richards, Burroughs, Thompson) under the blazing skullburning sun. But their intensive, immersive studies of early youth-flaming-out did not prepare them for what was to become their own position in the horrible, depressing nihilist dead rock star pantheon.

THIS ISN’T THE MELODY THAT LINGERS ON, IT’S THE MALADY THAT MALINGERS ON

And another quote from Bradfield:

“There was something almost David Lynchian in the lyric. I remember writing the song, thinking, ‘This is a bit Kiss In The Dreamhouse by Siouxsie And The Banshees’ – well, that’s perfect. That shard of beauty that can almost be shattered with one gust of wind is perfect for this.”

So let’s ease ourselves into the scalding acid bath of the song by taking that quote at face value. We can definitely hear what the singer-guitarist-songwriter means with his Siouxsie reference, as the album’s first song Cascade bears testament to:

“Scratch my leg with a rusty nail

Sadly it heals”

Immediately, with just those two lines, we know we are in the presence of a disturbed, disturbing, despairing, tragic mind. Why would somebody scratch their leg with a nail that could give them tetanus and gangrene and maybe even kill them…and actually want that to happen? Why would they be sad it heals? Clearly they are not happy with themselves, are somewhat divorced from reality, and are a danger to themselves. And maybe others. Instantly, of course, given the use of the first person, the song becomes autobiographical, and we can’t help but think of Edwards, with his penchant for cutting himself (the infamous 4 REAL incident et al), and how this is some sort of intimate, deeply uncomfortable portrait of the gory auto-abattoir of his feverish bloodstained mind.

It’s interesting – and telling – that the song is done in the present tense. It would not be written that way, of course, if it was indeed the nostalgic, warm, fuzzy, dimming-eyesight glowing look back at fond childhood memories claimed by Edwards. How can memories of gouging into your leg with a piece of rusty iron be regarded as ‘fond’, unless you are clearly not in your right mind?

NOTHING REALLY MAKES ME HAPPY

It’s truly strange being thrown into the deep end of an upended mind like this. What are we supposed to think? Why would Edwards write this sort of stuff? For attention? To shock people? To shock his band members? To let us know how horrible he was feeling, and how badly he was doing? None of these things? Some of them? All of them? And why would the band entertain him in putting music to such a bizarre and deranged creation, in effect encouraging him? That is why I examined what Wire and Bradfield said about the song above.

It could almost make you question whether certain topics should be addressed in art except, of course, that that would be censorship, impossible, and ludicrous. It would also laden the band with malintent towards the listener that they might have paraded in the past, for shock schlock yawn-who-cares ‘controversy’. But this was taking things to a whole different level altogether, digging up bones in a whole new disturbed aesthetic graveyard. Quite simply, this band had absolutely no idea whatsoever what they were doing when they produced The Holy Bible, which is what makes is so great, so timeless – and so scary and resonant and disturbing.

Nothing unfamiliar is easily grasped when artistically (still)born, and there had never been – will never be – another album like this in the history of the human race. So how were they to know they were making mad, artistically unassailable, lasting musical history, despite all the damaged, depressed artistic immortal influences they had grown up with? They couldn’t. They are blameless. Mostly. They wanted to create a timeless, deathless work of genius art, they did…and Hell mend them for getting what they asked for.

Be careful what you wish for, and other sinister-in-retrospect clichés.

DON’T KNOW WHAT I WANT BUT I KNOW HOW TO GET IT

“There are so many myths in rock’n’roll and we were steeped in them. I remember Richey going missing, and then two weeks later, just thinking, ‘Oh, is this it? Are we that story now?’ These things happen in rock’n’roll. I remember thinking, ‘Wow, it’s us. Fuck. It’s us.’”

- James Dean Bradfield.

And then the next odd lyrical couplet;

“Colour my hair but the dye grows out

I can’t seem to stay a fixed ideal”

The word “ideal” is drawn-out, distended, wailed, a mournful lament at the thought of an eternally unattainable eternal beauty. It’s another couplet in the present tense, belying any supposed backwards-gazing wee laddie nostalgia. You wonder if Edwards himself ever believed that flimsy no-not-right-now cover story, a mendacious figleaf covering a huge insanity-swollen mental maggot colony. Edwards is writing about himself right at that moment, talking about things he was doing right then in his life. And the chronology gets a bit non-linear, as it was in the first couplet. He’s scratching his leg and colouring his hair, but he already knows how these activities turn out – his leg heals and his hair goes back to its natural colour. It’s almost like he’s contemplating the futility of something he’s doing time and again and expecting a different result. And he will never, ever get a different result.

Because he’s trying to vainly and pointlessly fight the existential march of time itself, trying to stay dry in the always-raining storm of life. Raindrops keep falling on his dyed head, and that does mean his eyes will soon be turning red. He can’t stay an immature, arbitrary perfect fixed point (of no return) in the always-forward-moving inferno of time and life itself. It’s Wrong, quite simply, what he is thinking and doing. In an odd way he does stop time, by nailing his words to songs that will always be here. The Holy Bible is an album where people, both victims and victors, go against the grain of all healthy, sane human history, be they serial killers, prostitutes, anorexics, sex-addict dictators, self-mutilators, Nazis…who-and-whatever.

ALWAYS SHOULD BE SOMEONE YOU REALLY LOATHE

On The Holy Bible, Manic Street Preachers are making horrible charnel house artistic history by being

flung about by the unforgiving, merciless winds of undefeated, undefeatable

time, leaving bloodsprays and fingernail-gouges and slowly-receding screams

etched along the implacable voyeur walls of life eternal scorched. It’s an

album of pure madness and misanthropy and hatred and slaughterhouse laughter,

self-loathing writ large, a band led over a cliff by a deeply troubled

individual, a man whose central paradox would be that he professed to be

sensitive and to care about people, but who mercilessly victimised himself and

threw dictators and dictated-to alike onto butcher’s hooks to hang limp and

bleeding and pleading in the butcher’s shop of history and his mind.

It’s not

right, or tolerable, or sane, or fair, but, as one of the band’s dipsomaniac

literary heroes, Bukowski, put it, “Fair is just a dictionary word.” No mercies

or concessions are given, and in the end it’s just a huge, writhing, howling,

bleeding, pleading mess of fleshgash and bloodspurt and pitiless blank insect

doom horror, a modern Munch running screaming from nothing but the insane internal gaze itself.

Hieronymous Bosch would have done the cover for The Holy Bible is had he been

alive. Or at least he would have wanted to. The whole of The Holy Bible was a 4 REAL gouge along

the confused drivel-dribbling side of Britpop, a Bernard Herrmann shower-stabbing

soundtrack to a human race-slasher film. Where bands like Blur and Pulp and

Elastica and Supergrass and Oasis were cavorting being all Nu-Brit-chic, a

group of societally devastated Welshmen roared up out of the English troubled

conscience to be the Banquo at the post-Thatcher Cool Britannia vapid popslop

feast. These parochial metropolitan vermin had destroyed where the band had

come from, and they were not about to let them forget it.

WHEN THE DEAD WALK SENORES, WE MUST STOP THE KILLING OR WE LOSE THE WAR

And then:

“Childhood pictures redeem

Clean and so serene

See myself without ruining lines

Whole days throwing sticks into a

stream”

The word “stream” is howled in a deranged, madness-wallowing falsetto. Edwards

is always looking back for solace from the modern adult world, to be ‘redeemed’

by childhood innocence recalled once more. “Clean and so serene” is both a

poignant and a viciously, hatefully mocking line. ‘Clean And Serene’ is the

motto of the Betty Ford Clinic, a substance abuse facility opened by the wife

of former US President Gerald Ford. By the time he wrote this

song, Edwards had already been in a health farm a couple of times for his

drinking. So him recalling the BFC motto is a deeply cynical, sarcastic swipe

at being cleaned up, and also a pining, poignant longing for being “clean”,

paradoxically by being in the “soil” of childhood. Which was never in his childhood

anyway. You know what I mean.

As noted by Yusef Sayed on his excellent, authoritative, head-hurting Holy

Bible analysis site 227lears.com (check it out if you are a fan of this album,

and haven’t seen it already – you won’t regret it), the ‘lines’ being referred

to may be the lines on Edwards’s skin that he has carved with the rusty nail.

But if they are, how can he be ‘redeemed’ (a religious concept) by having

‘ruined’ himself by scratching them onto his flesh in the first place? The cure

is the disease. If, by injuring himself, he has ruined

himself, there is no redemption (“there is never redemption/any fool can regret

yesterday”, as Archives of Pain from the same album puts it) to be had in his

treasured childhood memories…because even those images contain pain and self-ruination.

There is no escape.

Ever.

The past is a ghostly foreign country, and a nice place to visit – but you

wouldn’t want to live there. The “lines” line could also, potentially, be read

as a comment about Edwards’s own writing never being as good as he wanted it to

be, and looking back to a time when he had not started writing and ruining

lyrics and poems by getting them inexact, wrong, just not slightly right.

Could read like that.

Or maybe not.

Your guess is as good as mine.

Follow this link to the second and concluding part of the piece:

https://whorattledyourcage.blogspot.com/2025/02/die-in-summertime-part-2.html

Comments

Post a Comment